No. 246 November 2024

- COVER REVIEW: Sforzato DSP-07EX ⸜ audio file player » JAPAN

- KRAKOW SONIC SOCIETY № 148: SILTECH MASTER CROWN » POLAND ⸜ Krakow

- REVIEW: Aura VA-40 REBIRTH ⸜ integrated amplifier » JAPAN

- REVIEW: Phonia GRAVIS 400 ⸜ loudspeakers • floor-standing » POLAND

- REVIEW: Stage III Concepts A.S.P. REFERENCE LEVIATHAN LIMITED EDITION ⸜ power cable AC » USA

- REVIEW: TiGLON MS-DR20R ⸜ analog interconnect RCA » JAPAN

- MUSIC ⸜ Our Albums Series: MILTON NASCIMENTO & ESPERANZA SPALDING, Milton + Esperanza, Concord Records UCCO-1243, SHM-CD ⸜ 2024 » USA / JAPAN

- MUSIC ⸜ Our Albums Series: HANG RAIJI Plus Five, Electric Bird/ Step Records STPR-044, UHQCD ⸜ 1983/2024 » JAPAN

- MUSIC ⸜review: JOHN LENNON, Mind Games (The Ultimate Mixes), Apple/Universal Music Group International, 2 x SHM-CD ⸜ 1973/2024 ˻ PL ˺

|

Welcome to Poland! I’ve got an overwhelming impression that Poland is a country of great potential. A usually unfulfilled, highly dispersed potential lost as heat energy through friction, and mostly converted into kinetic energy only outside the borders of our beautiful country. If I mentioned – in no particular order and without previous preparation – surnames such as: Penderecki, Wieniawski, Górecki, Chopin, Lutosławski, Mykietyn, Komeda, Stańko, Możdżer (music; composers and performers), Zbigniew Jastrzębski, Marek Karewicz (graphics; album covers), Stefan Kudelski (audio equipment, manufacturer), to name a few, most audio-related people – all of them have one thing in common: their careers went into full motion only after they left Poland. It’s as if their greatness could only be authorized after getting a glance from foreign eyes. For some time now, however – though this may be my personal, subjective opinion – things have been changing, and you don’t need an external “imprimatur” as strong as you did before to properly judge and appreciate someone’s worth. These changes are coming on very slowly, though.

There’s a similar situation when it comes to audio products. I’ve already mentioned the Polish company Nagra, or rather its founder, Polish engineer Stefan Kudelski (1929-2013) who emigrated with his parents through Romania to France in 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland, to finish studying there. It’s also worth adding Wally (or actually, Waldek) Malewicz’s last name to the list (MS MechEng; also see HERE), an analogue specialist. There are few such examples, however – very few. And when you ask about the Polish market, now and then and in the past 50 years, it will seem like a black hole. And in some ways, if it’s hard to think of something you can put a finger on, or some names and people to bring up from this time period, you know you’re in trouble. One of the reasons for this is Polish history. When it comes to the People’s Republic of Poland, many myths exist, and they’re very often contradictory. For example, there’s a belief that nobody worked in the PRP, that people fundamentally slacked off. But there’s also a belief that it was a time of hard toil that brought with it nothing but humiliation. In the light of the former, the “Solidarity” revolt would be pointless, while in the light of the latter, all the common sayings like “they pretend they’re paying us, and we’re pretending we’re working” or “if you work or play, you’ll still get your pay” would be impossible. But one thing is understandable and definitely true: it was a country of immense contradictions and a complete lack of logic – wrote Dorota Jarecka in her review of the “Free time. Photography” exhibition (Dorota Jarecka, Czas artysty, czas robotnika, Gazeta Wyborcza”, August 19th, 2013). It’s hard not to agree with that, to not notice the double standard of that time period, when people tried to live normally on one hand, but fought on the other; on one hand, all effort was made to stand against the authorities, and on the other – people strived to rebuild the country. This double standard will surely remain part of our history forever. And it’s impossible – as I see it – to work out one, common view; we can’t write a history textbook about it. But maybe, and I’m looking at it from an audio perspective, I’ll do something else – I’ll try to dig up what’s important and matters more in terms of aesthetics than politics: the history of Polish technology and design. I’d like this short editorial, and the articles contained within this edition of “High Fidelity” to be prompts for a wider discussion on this topic, and – with a little luck – help rebuild our identity. PREHISTORY

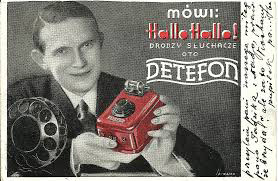

The story of Polish broadcasting industry begins after World War I. The book, An outline of Polish electronic industry up to 1985 suggests an exact date: the 1st of February, 1925, when the first prototype radio station was opened in Warsaw, at 29 Narbutt Street. A year prior, the “Polish Radio ltd” company was founded (Mieczysław Hutnik, Tadeusz Pachniewicz, An outline of Polish electronic industry up to 1985, Warsaw 1994). In 1939, the number of radio subscribers reached over a million. That obviously meant a huge demand for radio receivers. The primary producers were certainly Polish branches of foreign manufacturers such as Philips and Telefunken in Warsaw, but the Elektrit factories in Vilnius and the National Tele- and Radio-technical Workshops in Warsaw were also important. In 1939 the number of radio engineering industrial facilities rose to 34, employing 6150 workers. There were 120 engineers among them. Except tube radio receivers, whose design is known to all, the Detefon was a noteworthy product of that particular era. This Polish radio receiver was equipped with a crystal detector and worked on long and medium wavelengths

The radio didn’t have a built-in amplifier, and high-impedance (2000 Ω) headphones were required for playback. The machine was designed by Wilhelm Rotkiewicz in 1929. Half a million units were produced until the breakout of the war. What’s important, the well-known artist Poliński was responsible for the Detefon’s design. Headphones are a pretty uncomfortable way of listening to a stationary radio, which is why except the receiver, active speakers were also released: the single-tube Amplifon and dual-tube Binofon Z and Binofon B with a different visual design (“Old Radio” and HERE). It’s worth noticing the Amplifon’s beauty – both its front and rear panel, with the ‘f’ shaped cut-outs, imitating the ones you find on violins. It’s the first example of successful cooperation between Polish engineers and designers in terms of audio products that I’m aware of.

FONICA

World War II (accepted as the period of time between September 1st, 1939 and May 8th, 1945) is a dark time in Polish history, and national production was subordinated to the needs of the Nazi invaders. Polish industry re-starts even during the war, however, and as early as May 1st, 1945, the State Tele- and Radio-Engineering Plant was summoned to life. In the same year, the State of Tele- and Radio-engineering Plant in Łódź, on 9 Skrzywana Street (later transformed into the Telephone Manufacturing Plant T-4, then Fonica, and eventually Unitra-Fonica) was founded, and a year later the Speaker Factory in Września near Poznań (later known as Tonsil) followed.

Unfortunately, we don’t know the names of the designers of the first Polish turntable. The GE-53, launched to the market in 1954 by the Telephone Manufacturing Plant. Interestingly, there is a discrepancy between the name pointing at the year 1953 and the actual market launch a year later; one of the trails may be the fact that sapphire cartridge styluses were only manufactured from 1954 onward and were a part of this first fully Polish turntable design. Another hint may be its very close similarity to the HX301A from Philips (see HERE). Not much was changed in this respect by the GE-56 launched in 1956, or the Karolinka turntable, manufactured between 1957-1961.

DIORA

The cooperation between Piotr Tworz (1935-2000) and Janusz Zygadlewicz (1931-1987) turned out to be much more important. Piotr Tworz was an engineer and designer of radio receivers, working in Diora production plant from 1957 onwards. And Diora is the second, right after Fonica, most important Polish audio manufacturer. Summoned to life on the 8th of November, 1945, called the State Factory of Radio Receivers (PFOR in Polish) in Dzierżoniowo, it changed its name several times – the South-Silesian Radio Device Plant, T-6, only to finally become Diora. In 1947 a license for a radio receiver was bought from the Swedish company AGA, sold under the name Aga in Poland. A year later, after manufacturing 25,000 of these radios, we had our first fully-Polish product, the Pioneer radio, produced under the name Promyk up to 1968. The company’s main engineer, Mr. Wilhelm Rotkiewicz, was responsible for their creation.

Janusz Zygadlewicz’s last name doesn’t appear in this story by accident. He was a costume and stage designer, and worked in the Motor Industry Construction Bureau in Warsaw between 1956 and 1959. He’s best-known as the author of the bodywork for the Smyk car, for the Szczecin Motorcycle Factory (1957) and the electric Melex vehicle for the Telecommunication Equipment Plant (1970). His design of a photo camera for Hasselblad in 1969 is equally interesting, although far less known. His biography is, however, important to us, to the audio world. In 1962-1970 he cooperated with the Diora Radio Factory in Dzierżonowo, with Piotr Tworz. He designed the exterior of the Rytm (1967) and Ewa (1969) radio receivers. The latter was the second (after the Izabela) Polish radio with a FM range. Piotr Tworz also worked out, for example, the Alina receivers, and the Zodiak DSS-401 and Tosca receivers. The Ewa receiver was used during the Polish expedition to the Himalayas in 1971, and I myself used the Tosca in my high school years… |

In 1972, the first Polish hi-fi class radio receiver, called Meluzyna, was presented. Described by its manufacturer as the “Meluzyna TST-101 hi-fi receiver (tuner)”, it was the best radio receiver in Poland, in its time. Because it was a prestigious product (‘1st class, with 1 finish, representing top-class radio receivers, fully-transistor and stereophonic’) all the usually-omitted elements were taken care of in great detail, such as the FM head with a separate oscillator, with a module of automatic frequency regulation, a four-step intermediate frequency amplifier, among many others. The tuner was part of a system that also comprised of the WST-101 amplifier, the WG-610f turntable and amplifier, and the ZK-246 reel-to-reel recorder and amp. There was also a list of Tonsil speakers it could be paired with. The most expensive one was the ZG-30C, which cost 2300 zlotys. The Meluzyna cost 3200 zlotys, and a complete system sold for 12,000 zlotys. At the same time, in cooperation with Japanese company Sanyo (Tokyo – Sanyo Electric Co. Ltd) Elizabeth, a modern stereophonic receiver, was built. It is said that the start of its manufacturing in 1973 brought in notable technological advancement into Polish electronics. For the first time, it used modern components like integrated circuits, thick-layered circuits, LEDs, and ceramic filters. According to the Information on stereophony. Home audio devices in 1973/1974 brochure (“WEMA” Industrial Machinery Publishing House, Warsaw, 1973) the “Elizabeth-Stereo” radio receiver is a: Mieczysław Białek was responsible for the mechanical construction, in turn. There were two versions of it on the market; an older one with a green scale backlight and a newer, red one. I know this because I owned both of them and both of them had one dead channel. As it turns out, the power amplifier was built using thick-layered integrated circuits, produced by Telpod in Kraków. Years later, I did some work experience in the very same division of the factory. Life’s all one big circle.

It would seem, then, that we can be proud of the Polish audio market. However... Clearly, the need for new things was stronger and music lovers, as well as “ordinary people” looked to the West with greedy, hungry eyes, regarding Polish equipment as something worse. It seems that to cater to these needs Aleksander Witort, valued for his popularization of audio technology in Poland, in his 1973 book-guide Stereophony for all chose photos of the following brands for illustrating his book: Elac, Dual, Riga (not to be confused with Rega), and Goodmans. And not a single illustration of a Polish device. Not to leave Mr. Witort in a difficult situation, I’ll add that the authors of Electroacoustic amplifiers (Maciej Feszczuk, 1978) and On stereo and quadrophonics (Leopold B. Witkowski, 1990), did exactly the same thing.

The fall of Diora happened in 2001, and in 2006 it was erased from the court documents. A year before that there was an announcement that Robert Waldemar Kubaś, Mariusz Piestrak and Piotr Burzyński bought the company’s logo from the trustee and were preparing a new tube amp. However, in 2009, something completely different was released onto the market – Chinese electronics and speakers. Distributed by the Manta company. KASPRZAK Let’s go back to the topic of Janusz Zygadlewicz, though. The 1972-1978 period was when he worked in the Kasprzak Radio Plant in Warsaw. Opened in 1951, it was the first Polish factory designed and built with radio engineering in mind. At first, the amount of work versus workspace was disproportionate, so two other production plants were moved onto their grounds. Because the factory didn’t have the ability to manufacture components, it had to cooperate with the T-4 factory in Łódź, a.k.a. Fonica, to get them. The most famous radio receiver from those years is the Stolica. For a short time, between 1952 and 1954 they also produced dynamic speakers, on base of a license bought from AGA-Baltic. Production was moved to the factory in Września (Tonsil) in 1954.

There is a designer’s pearl among them – the ZK 146, designed by Janusz Zygadlewicz in 1974. The enclosure was made of perforated metal sheet with round holes, and resembled what the designer had done earlier with the Ewa radio receiver. Describing this unique designer, Anna Maga (Rzeczy niepospolite, p. 284) speakes of a characteristic, rectangle “architecture” of the ZK 146 chassis, dominating in the 1970s. That referral to architecture is not accidental – the discipline was close to Zygadlewicz due to his profession. And she continues:

The manner of body design – a rhythmic, “raster” decoration of speaker drivers, or the arrangement of knobs and buttons – bring to mind irresistible connotations with elevation division of buildings from that era. Stylistic changes from that time – both in industrial design and in architecture – were dictated, apart from changing aesthetic preferences, mostly by technological advancements. Enclosures of radio engineering devices were usually made of bent metal sheets.

In 1998, “Rzeczpospolita” proclaimed: THE 1970-1980 YEARS

Edward Gierek ruled Poland between 1970-1980, but the “golden age” is generally thought to be 1970-1975m when a wide current of foreign loans flowed into Poland, and – among other things – licenses were bought for the money. That’s how Fonika and Unitra, from Łódź and Warsaw respectively, began manufacturing in cooperation with Telefunken, Philips, Grundig, Sanyo and Thomson. At the same time, the West was going through a period of dynamic development, which the audio branch was also blessed by. A year before the first broadcast of the cult Polish series Czterdziestolatek, “The Absolute Sound” magazine was published for the first time, riding this very wave. It celebrated it’s 40th anniversary and 234 editions last month. In editorial materials, but also in the comments of companies that cooperated with the magazine at the time, one common theme is prominent: the magazine took many new, completely unknown, mostly-British companies under their wing. And there was a lot to choose from – two years prior, Meridian was founded, a year after the founding of Monitor Audio; and in 1973 alone, Rega, Accuphase, Electrocompaniet and Naim were founded. Around this time, the most interesting Polish turntables get onto the market: the G600, Fonomaster, Daniel, and later in the 1980s, the Adam possibly the best one. You can read about that in the Subjective history of Polish turntables article by Maciej Tułodziecki. In his words, Fonica manufactured over 80 turntable models. Despite that, very little is known about their designers and engineers, you can merely find some scraps of information: in 1980, the Łódź City Award was given to a team of engineers in the Łódź Radio Company “Unitra-Fonica”, and the team comprised of: Witold Bohdzian, Leon Bołdaniuk, Janusz Joński, Jan Kędziora, Marek Mierzwiński, Stefan Skoczek, Andrzej Skonieczny – for achievements in preparing and commencing the serial production of Hi-Fi turntables and amplifiers which followed international standards (read HERE), or that in the very same year the Artistic and Research Workshops of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts founded a concept study of an “integrated phonic set”. As they said: Under this complicated name hides a design of an audio set, prepared for permanent fixing into a piece of furniture. Its economical form followed the tendencies of audio-playback device designs of its time. The project’s promoter was Lech Tomaszewski (read HERE). And there’s also a fragment of the Polish Film Chronicles, directed by Sławomir Sławkowski and Bogusław Saganowski called From Bambino to Daniel ( Polish Film Chronicle 46/78, B release, 1978, 2:33 – 3:41, watch HERE)

CONCLUSION

The Radmor company has a seperate place in the hearts of Polish music lovers. Their best known (I believe) design was the Radmor OR-5100 receiver from 1977, designed by the famous Polish designer Grzegorz Strzelewicz, and Maciej Sokólski’s construction, the product of the cooperation of the Telecommunications Institute and the PTH Industrial Design Centre in Warsaw. As all people who know their stuff agree on, the so-called “Radmors” were the best audio products made in Poland before the “transformation”. And they’re still waiting for their story to be told. Much like the difficult 1980s. Let’s hope this niche can be filled in the future.

Let’s add that past 1989, a whole new period in the development of Polish audio began. All previously-produced audio devices, manufactured between 1945-1989 (for obvious reasons I’m omitting individual production and DIY) were meant for the mass market. In the 1990s and 2000s, as well as in the last decade, something very different was born – very expensive components, speakers and accessories intended for a narrow audiophile audience.

|

About Us |

We cooperate |

Patrons |

|

Our reviewers regularly contribute to “Enjoy the Music.com”, “Positive-Feedback.com”, “HiFiStatement.net” and “Hi-Fi Choice & Home Cinema. Edycja Polska” . "High Fidelity" is a monthly magazine dedicated to high quality sound. It has been published since May 1st, 2004. Up until October 2008, the magazine was called "High Fidelity OnLine", but since November 2008 it has been registered under the new title. "High Fidelity" is an online magazine, i.e. it is only published on the web. For the last few years it has been published both in Polish and in English. Thanks to our English section, the magazine has now a worldwide reach - statistics show that we have readers from almost every country in the world. Once a year, we prepare a printed edition of one of reviews published online. This unique, limited collector's edition is given to the visitors of the Audio Show in Warsaw, Poland, held in November of each year. For years, "High Fidelity" has been cooperating with other audio magazines, including “Enjoy the Music.com” and “Positive-Feedback.com” in the U.S. and “HiFiStatement.net” in Germany. Our reviews have also been published by “6moons.com”. You can contact any of our contributors by clicking his email address on our CONTACT page. |

|

|

main page | archive | contact | kts

© 2009 HighFidelity, design by PikselStudio,

projektowanie stron www: Indecity