|

TECHNOLOGY

BRIPHONIC: WHAT IS BEST

|

|

|

WORLD PREMIERE | BLANK

So, we have got used to, or at least I have got used to the fact that Japanese visionaries are treated like holy fools or yurodivy (Russian: юродивый, Greek: môros, Syrian: ţđîäčâűé) – we do not fully understand them, so we have to accept everything that they say, as in some time we will also get where they are now. Of course, these are people who perfectly know what they are doing. However, from the perspective of a “classic audiophile”, the actions that they take may seem to be extreme, which has led to the creation of a separate group of manufacturers.

Mayo Nakano next to the Bösendorfer Model 290 Imperial piano If we, audiophiles (the second layer), are treated by “common” people (the first basic layer) with reserve and suspicion, and the actions we take are compared to voodoo, the group that I mentioned above is seen in exactly the same way, but from our perspective, creating the third layer. For people representing the first layer, those belonging to the third one are the least rooted in reality. However, they actually make our audiophile world go around. These are the people that I would like to tell you about. The BRIPHONIC company run by Mr Masamichi Ohashi deals with recording and releasing music on CDs and pen drives. The way they act has all the characteristic features that I mentioned above: striving to make a vision come true at all costs, being curious and having an uncompromising attitude. At the same time, these people apply solutions regarded by most audio and sound engineers as nonsensical and often counterproductive: mastering on a 1” tape moving with the speed of 76 cm/s, recording and mastering in the DSD256 (11.2 MHz) digital domain, with material released not only on a classic Compact Disc, but also on CD-R, Gold CD-R and – it is an absolute premiere! – Extreme Hard Glass CD-R. With reference to two albums, we will tell you what they sound like, show you differences in sound and discuss the technical aspects of this type of recording. However, as Briphonic is a company that is deeply rooted in analogue technology, let us start with the history of the evolution of reel-to-reel tape recorders and the path that has led the company where it is now. | TRACK 1: THE HISTORY OF THE TAPE RECORDER At the beginning there was the tape. It is not the whole truth, but we will come closer to it if we add the words: “high quality recordings” to this sentence, which will result in: “At the beginning of high quality recordings there was the tape.” It is because recording on magnetic tape made unprecedented development of the art of recording possible. Tape has its roots in pre-war Germany and it was designed, as well as manufactured by the BASF company. The tape recorder that it could be used with owes its original form, i.e. one using alternating bias current modulating the signa;, to Nazi scientists. Their main aim was to broadcast Hitler’s speeches in many cities at the same time, but they would also broadcast classical music.

The Magnetophon K4 (photo: Reinhard Kraasch) That could have been one of those unused opportunities – if the army that occupied Germany had not taken devices called the Magnetophon both to the US and the USSR. As far as the USA is concerned, the person in charge of that operation was John T. Mullin, an engineer and audio & video specialist who was sent to Paris in 1944, where the army kept the devices. Among them, there were tape recorders called the AEG Tonschreiber Magnetophon, using tape that was a little over ¼” wide, moving with the speed of 77 cm/s (30.3 inches per second). However, the sound quality of those devices was not high and it did not exceed the quality of a phone talk. Everything changed when Mullin met a British officer that he shared his love for music with. Thanks to him, Mullin got to a small studio in Bad Nauheim, north of Frankfurt, where he found the AEG Magnetophon characterized by sound quality that he had not even dreamt about – it was found that those devices used alternating current bias. Mullin managed to convince his superiors to let him send, for his private purposes, two K-4 tape recorders and 50 clean BASF and AGFA PVC Luvitherm Type-L tapes to the USA. When he returned to the country, he quickly demonstrated the invention to the Ampex Corporation in San Francisco. The company was interested in it and soon it built its own tape recorder, the Model 200, based on the German device. One of the people who were especially interested in it was the musician and singer Bing Crosby. In 1947, he hired Mullin to record his radio performance and bought the first two Ampex tape recorders for the enormous sum of 50,000 USD, contributing in this way to financing research carried out by the Ampex company and to its rapid development. | TRACK 2: SIZE DOES MATTER The constant values for tape speed and width that were established at that time became the official standard. They can be checked on the website allegrosound.com in an article entitled Tape Replay, EQ & Head Standards. The following values were accepted then for reel-to-reel tape recorders: 30 ips (76.2 cm/s), 15 ips (38.1 cm/s), 7½ ips (19.05 cm/s) and 3 ¾ ips (9.53 cm/s). For the sake of simplicity, speed values in cm/s were rounded. Please pay attention to the fact that although the tape recorder originated in Europe and tape speed values were originally established using the metrical system (centimetres per second), since 1947 the values have been defined using the imperial system (inches per second). The only small exception to the rule was the Dutch invention – a cassette player with 4.75 cm/s tape speed, i.e. 1.875 ips.

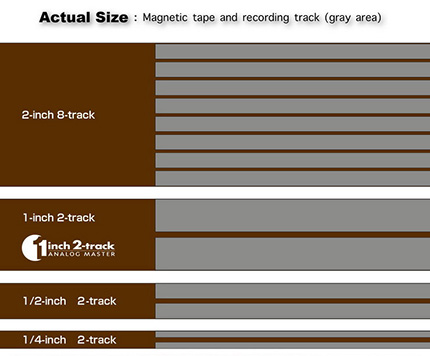

A comparison of the width of tapes and tracks on magnetic tape In home conditions, the lowest of the available speeds were used, i.e. 3¾ ips (9.53 cm/s) and 7½ ips. Recording studios used 15 ips (38 cm/s) and 7 ½ ips (19 cm/s). However, on the website of the Simon Fraser University (in the Tape Speed tab) we find a sentence that will be especially important to us: “One can also occasionally find tape recorders working at the speed of 30 ips (76 cm/s).” Where do so many tape speed values come from? Why did not they focus on just one? The answer is really simple: the higher the tape speed is, the broader frequency response and the lower THD, wow & flutter and noise are obtained. Theoretically, the highest speeds should have become the common standard, yet that did not happen because of the high cost of tapes and the technical features of tape recorders. It is not necessary to comment on the former cause – increasing tape speed twice doubled the cost of tape. The latter is more complicated. An analogue tape recorder is not a device which records and produces ideal sound. It was important for sound engineers that frequency response changes alongside changes in tape speed. On the one hand, the higher the speed is, the broader the frequency response (at its top), but, on the other hand, bass is less linear (sometimes it is boosted and sometimes suppressed) and it decays more quickly. This is common knowledge and that is why some recording engineers choose 15 ips (19 cm/s) tape speed, claiming that sound is “thicker” and “better filled” thanks to that. However, in 1997, Mr Tim de Paravicini presented a stereophonic tape recorder working with z 1” tape and tube electronics. The system was a prototype of the system used in Briphonic devices. A comparison of frequency response values measured for different tape speeds can be found in an article entitled The Unpredictable Joys of Analog Recording on Jack Endino’s (a producer and sound engineer) website. He made an effort and analysed how tape recorders manufactured by different companies, both multichannel and stereophonic ones, operate at different tape speeds; he was interested only in two values: 30 ips (38 cm/s) and 15 ips (19 cm/s). His diagrams clearly show that proper tape recorder calibration and the choice of a specific model are the most important here. The best results were obtained for Studer tape recorders – the A80 MkII, A820 and A827, as well as the Ampex ATR-102 tape recorder. STUDER

The Studer A820 tape recorder In 1949 ,Willi Studer developed his first tape recorder called the Dynavox. When he established the ELA AG company in 1951 with Hans Winzeler, the device got a new name: the Revox T26. The Studer 27, as it is also called, entered mass production in 1952. In 1960, a new model, the C37 was presented, having specs that are still considered very good today. In 1964, the production of its four-channel J37 version began. It was used in EMI studios to record The Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. A 24-track device, the A80 model, was launched in 1970 and the first tape recorder controlled by a microprocessor (the A800 model) was presented in 1978. Its most advanced version was the A820 from the year 1985, after which Studer focused on the digital domain…Another parameter connected with recording on tape is its width. You may still remember – tapes produced by German companies were a little over ¼ inch wide. It was accepted in the USA and adapted to the system that was used there – since that moment, tape was to be ¼ inch wide. It was used to record monophonic signal over its entire width and later also stereophonic signal, dividing tape into two tracks. Problems occurred when, in 1953, 8-track tape recorders appeared thanks to Les Paul. The narrower a magnetic track on tape is, the weaker its parameters, i.e. the higher noise and THD, and the less linear frequency response is. Alongside the development of this type of recording, tapes were becoming wider and wider – first 1/2” and then 1” and 2”. Actually, 2” tape width was only used in 24-track tape recorders. | TRACK 3: BRIPHONIC In this way, we get to the point of this article – solutions used by Briphonic. I have already mentioned that the company belongs to the category of “holy fools” , i.e. it does more than even the most non-standard companies from the audiophile circle. In its search, it has gone both towards the analogue and digital domain, and we will look at the process using two albums as examples: Sentimental Reasons and MIWAKU, both containing music of the Mayo Nakano Piano Trio. Mr Masamichi Ohashi, the owner of Briphonic, was responsible for both recording and mastering the albums.  MASAMICHI OHASHI WOJCIECH PACUŁA: What does BRIPHONIC mean? Please tell us a few words about yourself

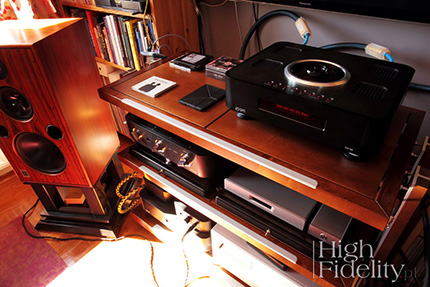

A system used by Mr Ohashi-san What audio system do you use?

In what respect, do you think, is 1” tape better for stereo signal than the standard ¼”? And where does the 76 cm/s speed come from? What mixing table do you use? What microphones do you prefer?

I can see that in some recordings you use the Cesium Atomic Clock, and in other ones – e.g. for the Sentimental Reasons and MIWAKU – the Rubydium Atomic Clock – how do you choose? What are the differences in sound? What are the available forms of Briphonic recordings? Does it mean that recording on a Glass Master CD-R is the best? |

Your CDs feature the Direct Cutting logo – what technology does it refer to?

Are you thinking about vinyl records with the Briphonic logo?  The Sentimental Reasons album was recorded in a large hall (“Hall Recording”) onto the 8-track Studer A827 tape recorder (“Analog Multi Track Recording”) modified by Mr Masamichi Ohashi. The highest available standard tape speed, i.e. 30 ips was chosen and the widest available tape was used, i.e. 2”. It is an absolutely unusual combination, as ½” tapes have been used for 8-track recordings. Four times wider tracks minimise noise and distortion. Let me just add that all the music recorded on the album was played by all the musicians together.

The 24-track Studer A827 tape recorder with an 8-track head Signal was then mixed, mastered in the analogue domain and recorded on the stereophonic “master” Studer A80 Mk. IV (“Analog Master Recorder”) tape recorder. Both of the tape recorders are called the “Monster Analog Machine” in the literature, because the former makes 2-inch wide tape turn and the latter… The latter is even more interesting, reaching the limits of what is available at a studio. The tape speed of the master tape recorder is 76 cm/s and the device uses 1” wide tape! 1-inch tape used for stereophonic recording is something new to me. ¼” master tapes are commonly used and some recordings are made on ½” tape – some master copies of Depeche Mode albums are available in this form. But 1”? And 76 cm/s? That means very high costs and the necessity to process sound in order to bring back the bass, which, as it was demonstrated by Jack Endino, constitutes the biggest problem while recording at a high tape speed. Let us add that the following microphones were used for the recording: the Neumann M50 for the Bösendorfer Model 290 Imperial piano, the Schoeps MK4 with the M222 tube preamp for the bass and the Neumann TLM170i and KM84, the AKG 451 and the Sennheiser MD421 for the drums. Digital signal was edited in the Merging Technologies PYRAMIX Ver. X DAW.

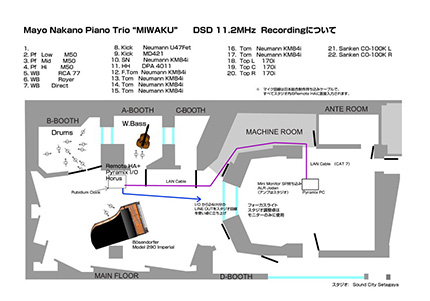

The Studer A80 MkIV tape recorder with 1-inch tape MIWAKU was recorded in a different way. It was assumed from the beginning that it would be a digital recording. Similarly as in the case of the Sentimental Reasons album, where an extreme version of an analogue system was used, this time Briphonic also chose solutions that seem unnecessary to most audio and sound engineers. Material was recorded onto eight tracks in the digital DSD256 (11.2 MHz) domain and in this form it was mixed and mastered (DSD Mastering, i.e. DSD Wide). Stereophonic DSD 11.2 MHz signal was obtained in this way. There are six tracks on the album, of which four were recorded at a studio and two during a concert. So, this is everything about how the albums were recorded. It is impossible not to admit that the company “went all the way”, using absolutely unique solutions. Of course, it is not the only firm that has striven for perfection. It is necessary for us to recall that, in the first half of the 1970s, the record label called Three Blind Mice (absolute perfectionists) looked at solutions using increased tape speed and LPs featuring a large 76 cm/s logo entered the market quite quickly.

TBM adopted a different strategy, however – the 16-track 3M S-72 tape recorder worked at a double speed. The thing was that it was necessary to include as many as 16 channels on broad tape and increasing tape speed significantly improved the S/N ratio. The mastering tape recorder used was the Philips PRO-51, operating at the traditional speed of 38 cm/s. Burning a master copy for a CD directly from a DAW had also been “practised” by the JVC company – see the Okihiko Sugano Recording Collection XRCD24. However, such a combination of a few top-of-the-range technologies is something unique. | TRACK 4: SOUND The method of releasing the material is perhaps even more interesting than the recording method. As Mr Ohashi-san said, both albums are available both in the PCM 16/44.1 format and in the form of DSD128 and DSD256 files. The available CDs are: a classic Compact Disc (¥3500 ~ 115 PLN), CD-R (¥7000 ~ 230 PLN), Gold CD-R (¥10,000 ~ 330 PLN) and Glass CD-R (¥100,000 ~ 3300 PLN); all of the prices given do not include VAT, duty and shipping costs. Let us look at the CDs this time, leaving a comparison with files on a pen drive (¥13,000) for a meeting of the Krakow Sonic Society. SENTIMENTAL REASONS

Compact Disc | The recording in its basic form sounds extremely expressive. The musical message is very natural, but also well-defined. Our attention is attracted by strong and clear treble characterized by high resolution. Bass is quite strong, but shown from a certain distance without contouring. It is a good move, although the bass sometimes lacks definition. The piano is the most important, however – with beautiful tone and shading. It is shown from a certain distance, which makes it more natural. Perfect, really exceptional dynamics also remains in a listener’s memory. CD-R | Shifting from a CD to a Master CD-R gives you a shock – always and everywhere. Even in this case, where the basic CD itself is great. The material on the CD-R is softer and warmer, with lower accent. The treble, which is simply very clean on the CD, now is not only clean but also natural, because it is better integrated with the midrange. The dynamics seems to be reduced, but it is because everything is less contoured and the attack is not marked as strongly as in the basic version. Gold CD-R | Sound with the “gold” version is even lower, as the double bass is more emphasised. But its decay is shorter than on the CD version, which makes it better. The treble is stronger than on the CD-R and resembles what we get with the CD, but with all the advantages of a “Master” disc, i.e. softness and resolution. Sound seems calmer than on the CD-R and much calmer than on the CD. But only now, in such a comparison, one can hear that this is THE version and THE sound – very natural, relaxing and at the same time dense within itself, natural and thick. Glass CD-R | I have been impatiently waiting for this version, as I had never listened to a Glass CD-R before. I did listen to Glass CDs and Crystal CDs, but not to their recordable version. It would be the easiest to say that it is the best and wins over everything else. However, it appears that it was no coincidence when Mr Masamichi Ohashi talked about personal choices in our mini-interview and did not say that a Glass CD-R is automatically better.

It is because sound with this version is the most open and without the warmth that makes the Gold CD-R version so pleasant and natural. When it comes to openness, tone and dynamics, the Glass CD-R version is closer to the “regular” CD. So, it is colder than the CD-R and Gold CD-R and more open than they are. One needs to listen to it for a longer time in order to hear what it is all about. The openness that I am talking about means incredible resolution. Due to it, it is possible for me to hear things that I did not hear before or did not pay attention to. The dynamics is incredible, as it combines the attack from the CD version with the filled and precise sound from the Gold CD-R. The double bass is still defined too weakly, I think. I understand it was about showing its real character and not what is heard by microphones – and that aim was achieved. However, the feeling of “here and now”, which we get with this instrument e.g. when listening to TBM recordings, is gone. What we get here resembles Rudy van Gelder’s recordings, but with a much better piano. The dynamics, resolution and openness are among the best I have ever heard from digital devices. MIWAKU Compact Disc | The first impression is related not to sound itself, but a specific character of these recordings – different than in the case of Sentimental Reasons. MIWAKU is a more intimate album, with instruments shown from a shorter perspective, closer. One may really like it.

One can also hear the specific character of DSD recordings. The sound is warmer and milder than with the Sentimental Reasons album. The attack has an incredibly attractive form, which makes the whole recording seem “tailored” to long listening and immersing oneself in music. The basic CD in the former session was really open and direct, while this one is closer to what we get with a turntable. What I am talking about is mainly the impression of thickness and low tonal balance. CD-R | The CD-R version is characterized by better resolution and shows instruments closer to us. However, as it shows reverb better, the proportions of everything also seem to be shown better. If earlier the instruments really materialised in our room, the studio where they were placed materialises with the CD-R version. The cymbals are still warm and dense, but the piano goes to the next level – it is larger, more dynamic and louder. The double bass is not that warm anymore, it is characterized by better resolution, but it is shown from a certain distance again, because of which there is not too much definition in its sound. Gold CD-R | The Gold CD-R version showed a warmer version of the recording before – this time sound resolution is higher than with the CD-R and more open. The piano is shown a little further away, because of which it no longer gives the impression of being warm and situated close to us. However, only now do we get the fullness and richness, “things happen” here not because of details and particulars, but thanks to information and saturation. This seems to be the least attractive version so far, but in fact it is the most dynamic, characterized by the highest resolution and simply the most real.

Glass CD-R | It is incredible how much this version resembles both the “ordinary” Compact Disc and the Gold CD-R! Its tone is lower than with the latter, but its resolution is the best of the whole set. The sound is not as close as with the CD, but it is not so warmed, either. The drums are the most dynamic and the strongest. The piano is shown further away, but has excellent dynamics and definition – only now can one hear a lot of flavours that were masked before either by the warmth or emphasised dynamics. It is an outstanding version, although for people with balanced systems, knowing how such instruments sound live. | BLANK The way Mr Masamichi Ohashi records and releases albums is unique and, unfortunately, reserved for few people. It is because it is incredibly expensive, consumes a lot of time and will never be profitable enough to be used by larger recording studios. However, it is the same in all industries on the top of what is possible – there are artists selling their products in small series, working in small teams, reaching a limited number of consumers.

However, those who will have an opportunity to listen to recordings with the Briphonic logo, will know what the digital reference sounds like – mainly in the field of CDs, but also in the case of files. It is even more valuable as we are talking about great music; such a combination must be particularly appreciated. From among all the versions that both reviewed albums are available on, the “golden means” is the Gold CD-R version. It has everything that we require from a Master CD-R and it is also incredibly musical. However, if you can afford to buy a Glass CD-R, you will hear what is really present in the recorded material. |

main page | archive | contact | kts

© 2009 HighFidelity, design by PikselStudio,

projektowanie stron www: Indecity

Japanese technical competence combined with in-depth devotion to a specific section of a given field have led to a situation where it is hard for the rest of the world to compete with this country in many respects. We have already written about many solutions – our admiration was usually mixed with disbelief. The admiration resulted from the fact that the actions taken contributed to much better sound that others can only dream of. On the other hand, in the name of reliability, engineers demanded explanations that they were either not able to find based on their classic academic education or, even if it they were, they did not believe what they found out.

Japanese technical competence combined with in-depth devotion to a specific section of a given field have led to a situation where it is hard for the rest of the world to compete with this country in many respects. We have already written about many solutions – our admiration was usually mixed with disbelief. The admiration resulted from the fact that the actions taken contributed to much better sound that others can only dream of. On the other hand, in the name of reliability, engineers demanded explanations that they were either not able to find based on their classic academic education or, even if it they were, they did not believe what they found out.