|

|

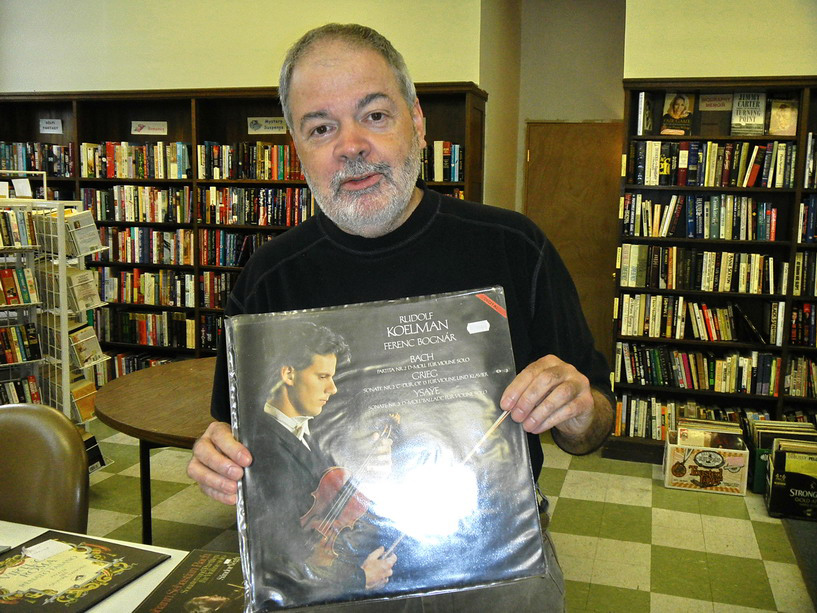

ave a look at the pictures in John Marx’s listening room. What do you see? What caught your attention? I was struck by the ubiquity of records and the ATC standmount speakers placed upside down. They point to John’s "out-of-the-box" thinking on the one hand and to his love for music. This is not just another audiophile with three CDs (samplers) to review audio components or someone who shudders at every single “non-kosher” detail.

John is, among other things, an audio journalist who has been running Stereophile’s Fifth Element column for years. His essays, articles, and reviews are different than what is usually found in audio magazines. They focus on the music and the man, treating the audio system as a necessary, viable and valuable tool, but a tool nonetheless which can be used well or poorly. The last thing you could say about him is that he "fetishes" hi-fi audio. His passion for audio gear is evident, otherwise he would not have spent time on it. But when he starts talking about the music everything else pales in comparison. ave a look at the pictures in John Marx’s listening room. What do you see? What caught your attention? I was struck by the ubiquity of records and the ATC standmount speakers placed upside down. They point to John’s "out-of-the-box" thinking on the one hand and to his love for music. This is not just another audiophile with three CDs (samplers) to review audio components or someone who shudders at every single “non-kosher” detail.

John is, among other things, an audio journalist who has been running Stereophile’s Fifth Element column for years. His essays, articles, and reviews are different than what is usually found in audio magazines. They focus on the music and the man, treating the audio system as a necessary, viable and valuable tool, but a tool nonetheless which can be used well or poorly. The last thing you could say about him is that he "fetishes" hi-fi audio. His passion for audio gear is evident, otherwise he would not have spent time on it. But when he starts talking about the music everything else pales in comparison.

As you are about to find out, my new friend is very well informed on the subject matter and has a balanced but firm opinion on the topics that fascinate him. This has resulted in the longest interview in a two-and-half year long history of interviews published in the "The Editors" series. Thirteen small print pages (10, Times New Roman), patiently answering my questions, sending next photos and showing interest in our correspondence (the interview has been via e-mail). And there was lots and lots to ask about, because apart from audio journalism John is also a sound engineer, and for some time he used to run his own record label, John Marks Recordings. He can therefore look at the audio industry from different points of view. As usual with such long in-depth texts, I encourage you to make a cup of tea or coffee, pour a glass or a pint, play some music and sit down for a relaxed reading..

John, please tell me something about yourself, about your childhood, career etc. Or to put it simply, how did it happen that you started listening to music?

As a very young child, I was fascinated by sounds. I had a music box that was a jack-in-the-box. It played the English folk song Johnny’s So Long at the Fair (also known as Oh, Dear, What Can the Matter Be?). I never got tired of the music. The pop-up puppet, I grew tired of.

My father was a jazz buff of the “moldy fig” variety. He adored Kid Ory and those players of the early generation such as King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton. I don’t think that he liked anyone more recent than that young upstart Louis Armstrong. My mother had taken piano lessons. During WWII, my mother’s brother had been a trombone player and singer with an Army Air Forces big band. He actually made some 78-rpm recordings, singing Same Old Dream and other love songs of that era.

My oldest brother got a folk guitar during the folk revival, and he sang. He too made at least one recording. But whereas my uncle’s big-band 78-rpm recordings truly were of professional quality, my brother’s track on a “showcase” LP called Rising Folk Stars of 1966 or something like that was, I think, not very good. He sang Dust My Broom, and it was not convincing.

And what kind of music did you listen to back then?

Well, back then the Catholic Mass was still in Latin, so every week I heard some Chant, some organ music, and some traditional hymns. Latin fascinated me. My oldest brother had a suitcase stereo hi-fi and an RCA record-club membership. I think that it was a requirement back then that everybody in America had to own Van Cliburn’s Tchaikovsky Concerto LP. It apparently was a patriotic duty. The Russians were first in space, but our guy could play Tchaikovsky! Even they had to admit it! My favorite LP however was the Charles Munch/Boston Symphony Debussy La Mer. Every time I go to Symphony Hall in Boston, it is a special thrill. BTW, Boston’s new conductor Andris Nelsons, from Latvia, is fabulous.

But most of the music was from the radio. I was not a huge fan of the Beatles when they came along. They were just OK with me until Abbey Road. The second side of Abbey Road was I thought something truly new—and worthwhile. Sgt. Pepper struck me as just a mash-up with a lot of music-hall music in it. McCartney’s posing got on my nerves, and I did not think that John Lennon was all that talented—so I was a music critic even before I had my driver’s license!

Did you have some decent audio gear?

Mostly suitcase stereos, growing up. My aunt and uncle had I think a Webcor, while my brother’s was a Motorola, I think. Nobody cared about properly placing the lid with the other speaker in it for “stereo.” Later on, I would put the player on the floor, take off the lid, and face the speakers toward each other and lie down with my head in between—that’s how I would listen to Simon & Garfunkel’s Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme LP.

My aunt and uncle’s stereo could also play 78 rpm discs, and so I listened to those, out of curiosity. The John Philip Sousa brass band, and of course Caruso. It was there I first heard the My Fair Lady soundtrack on 45-rpm records, a little boxed set of 45s. I used to sing along, thinking I was singing with Audrey Hepburn, not realizing it was the dubbed-in voice of Marni Nixon. Audrey Hepburn is still one of my ideals of feminine beauty.

When I reached third grade I was eligible for instrumental instruction in the public school, and so I chose violin. I was successful for a while. I just did what I was told, and played instinctively. I could play in tune with a big tone, but I was rather hopeless at subdividing the beat… or even basic counting. I was a principal second violin in a youth orchestra. The first time we all played together (there were probably at least 80 of us), I was so stunned by the sound we made—I have never forgotten that. I also sang in chorus—I was a boy soprano and my friend and I would annoy the girls by singing at least as high as they could and perhaps higher. Certainly louder.

To whom do you owe your first contact with hi-fi equipment?

A friend was an electronics hobbyist, and I learned from him. His parents had an all-in-one “console” stereo. However, the things that were the real “high fidelity” of the 1960s, original Marantz, and McIntosh and AR and Thorens, were out of our reach financially. We had kits from Allied Radio, we scavenged for old radio speakers, and we experimented with baffles and enclosures.

My first hi-fi had a plastic Garrard turntable and a Shure phono cartridge, and a solid-state integrated amplifier and ported two-way bookshelf speakers from Lafayette Radio. I later bought a Pioneer PL-12D turntable and a Pioneer integrated amplifier.

My first “high end” loudspeakers were I.M. Fried’s Q2s. But the first loudspeakers I heard that gave a “shock of recognition” musical experience were Chartwell (BBC) LS3/5As I heard at Nicholson’s in Nashville, Tennessee in 1977 or 1978. It was when I was living in Nashville that I first became aware of The Abso!ute Sound and the phenomenon of high-end audio.

What do you think is worthy of praise in today’s audio? What is bad?

I honestly think we have a crisis in high-end audio—let’s face it, there is a crisis. In the US we have gone past a tipping point—at least with regard to the “stereo-store business model.”

It used to be that too many stereo stores were chasing too few paying customers. Now the major dynamic is: Too many brands are chasing too few stereo stores. However, there are even fewer paying customers than before.

And, getting ahead of myself, the lack of showroom traffic in the remaining stereo stores is in my view the major cause of the explosion of hi-fi shows. I wrote about that in Stereophile (see HERE).

In the 1950s, there were lots of hi-fi shows, because there weren’t many stereo stores yet. The major US audio chains of the future such as “Tech Hi-Fi” (founded in a dormitory room at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), came about in the mid-1960s and hit their stride in the early 1970s. We are now at the tail end of that model, and so the hi-fi shows are back.

If you have a new audio company or are a new importer, signing up dealers is very difficult. So, if you exhibit at a hi-fi show, you might get a buzz going, and if people write nice things about your exhibit on the Internet, you can use that to try to sign up dealers.

When I was in college there were five stereo stores near the campus—now there are none there. But there are at least three tattoo parlors, and at least three eyebrow-threading parlors. So, I think that there is a crisis, and that we are with few exceptions in the endgame of the traditional stereo-store business model.

I think that the overarching and non-fixable cause of the problem is very simple: High-end audio is a victim of its own technological and marketplace successes. In the 1950s and 1960s, to get sound that was lifelike and not bloated in the bass and rolled-off in the treble, you had to be a hobbyist of sorts or at least know a hobbyist to give you good advice, and you had to spend some real money, or build a kit or two.

What has changed since the 1960s? First, the Thiele-Small parameters made it possible to predict the behavior of ported loudspeaker enclosures. Yes, ported enclosures can be built to “boom.” But not all of them do. We went from a situation where the good-sounding speakers were large sealed boxes such as the early AR speakers and the Larger Advent speaker, to a situation where there are very few sealed boxes—I just wrote about that in the June issue of Stereophile. [John Marks, Where are the sealed boxes of yesteryear?, “Stereophile”, Vol. 37, No. 6, June 2014, pg. 41-49 – Ed. note]. So one, by the late 1970s/early 1980s it became possible, almost overnight, to build a better loudspeaker for less money.

Second, large-scale integrated circuit chips. If you wanted to choose the music you heard in your home in 1959, you had to buy a stereo. Today, most people’s best sound system is in their car! And their smart phone can play their playlists. And their home theater can play music, and their computer can play music. Nearly everything everybody owns except their clothes-washing machine can play music. The basic technology for music playback fits on an inexpensive chip.

That is a total game-changer compared to vacuum-tube gear with point-to-point wiring in the 1950s. In the 1950s, a turntable, a vacuum-tube amplifier, and bookshelf speakers would in total weigh at least 50 pounds. An iPod and earbuds weigh a few ounces, and you can take thousands of tunes with you anywhere.

So today, to get people to want to buy a high end stereo, you have to convince people that the four or five things they already own that can play a CD or a music file are not good enough. Then, you have to convince then they have to spend a lot more money on a complete new system that is far less convenient to use than what they already have.

Do you think that inexpensive audio systems can also sound decent?

Have you heard the large Sonos speaker system, the Play:5? It costs $399 (plus some network hardware to connect it to your computer and through there to the Internet). That’s all the sound that most people want, because most people want music only as an accompaniment to other activities, and not as the sole focus of their attention.

If you just want some music in your home, just buy as many Sonos units as you need. However, if you want to hear everything that is going on inside a Beethoven Late String Quartet (or The Birth of the Cool), Sonos probably is not going to be good enough. You want stereo speakers set apart at least the width of a seated string quartet, and you want a convincing stereo image, etc. Well, not for The Birth of the Cool, perhaps. A sold center image would be nice, though.

So, the consumer-electronics industry as a whole is delivering a product—you and I might call it a generic product, but it is what people want. That product also sounds much better than the mass-market audio of the past. That is good. (I also think that the sound of audiophile gear is in general better than at any time in the past.)

However, the huge improvement in affordable mass-market audio means that today’s stereo-store stereo equipment has a tough job trying to make a convincing “value statement” to non-hobbyists.

A pair of high-quality two-way loudspeakers like Aerial Acoustics’ Model 5B plus Parasound’s entry-level CD player, preamp, and stereo power amplifier will cost a total of about $5000, including speaker stands and cables. I think that that system will deliver exceptional value for someone like me. But I also think that most normal people would rather spend the same amount of money on a cruise or other kind of vacation.

The complainers complain that “Stereophile” never gives any bad reviews. Well, that shows that they don’t read the magazine! I will say truly bad reviews are rare simply because there aren’t that many truly bad products.

There was a loudspeaker made about 40 years ago based upon drivers that Bose had rejected in Quality Control and then sold off for not much money. Quality-Control rejects! If I recall correctly, costing under four dollars per driver. That loudspeaker design was essentially an organ pipe with one four-inch driver at the top. Can you imagine anyone trying to sell that kind of thing today?

The cost to acquire very sophisticated capabilities in loudspeaker design, crossover simulation, and prototype measurement is perhaps 1/100th of what it was 40 years ago. Perhaps even less. Today, you really have to ignore a lot of freely or inexpensively available knowledge in order to build a loudspeaker that is just plain bad.

So, it’s a best of times/worst of times situation.

The high end is the victim of its own past successes in technology and marketing. Most people agree that good sound is “somewhat” important (but very few people are willing to make sacrifices in other areas of their lives in order to enjoy better sound quality). What has changed is that people no longer need to visit a stereo store to get sound that is good enough for them.

I think that there is going to be a shaking out, as more and more companies design ever-more expensive audio products on the theory that it is easier to sell one $50,000 pair of loudspeakers than ten pairs of $5,000 loudspeakers. Look what happened in real estate. Is high end audio a bubble?

Look at all the companies in Stereophile’s “Buyer’s Guide” that are offering loudspeakers costing more than $20,000 a pair. In other words, loudspeakers costing more money than most people spend on an automobile—an automobile that takes them three, four, or five years to pay off! I think there is going to be a shaking out.

I may be in the minority, but I absolutely can’t believe that just because somebody is rich, they are automatically going to buy an expensive stereo. Just look at the typical luxury goods. A Porsche 911. It stays in the garage. And even if all you do is, as shown in the TV commercial, drive your habitually late daughter to school after she intentionally misses her school bus, you have the experience of driving it, and the experience of being seen driving it, if you need that too. The Porsche does not live in the living room; it does not take up space in the home. (That said, reportedly the two most popular vehicles with US millionaires are the Ford F150 truck and the Jeep Grand Cherokee station wagon.)

A Rolex watch. OK. It takes up about six square inches on your dresser; you do not need to dedicate a room to it. People will react to it however they react. The Rolex is not something that one’s spouse will worry about the maid hitting with the vacuum cleaner, or, not vacuuming close to it and leaving dust on the carpet, both of which have been stated as objections to floorstanding speakers and arguments in favor of in-walls.

A wine cellar. OK, it’s in the basement.

Fine art takes up a little wall space. People can ooh and aah. Low maintenance. You walk past it and you see it. You don’t have to sit still in front of a painting for an hour, like you have to in order to enjoy a Mahler symphony. A passing glance is all that is needed.

Whereas when you are trying to sell a rich guy a $100,000 stereo system just because he is rich and not because he is a music lover, he pretty much has to dedicate a room to it, and he won’t get the full benefit unless he sits down in front of it and shuts up and pays attention. For hours at a time.

Does it make sense for someone to spend $100,000 on something he will use on average less than one hour a week? No.

The worst thing that is going on right now, in my view, is that the industry is migrating upward in price on the theory that “That is where the money is.” People seem to be afraid to release a product at $10,000 because the segment of the market they are targeting will think it does not cost enough; they seem to think it has to cost $20,000 before a rich person will take it seriously.

If the wristwatch business were a valid analogy to the stereo business, that thinking might be applicable. However, in the US at least (I can’t speak for China), the wristwatch business is not a valid analogy to the stereo business.

By the way, the streets are full of millionaires wearing $20 Timex watches as they drive their Ford pickup trucks. Millionaires in unglamorous businesses like dry cleaning, pouring concrete foundations, or selling plumbing supplies to builders.

I think that the rich guy who wants to sit at home and listen to music really deeply as the sole focus of his attention is the rare exception, and certainly not the rule. Alec Baldwin might listen to Mahler and he might even be crazy about Mahler (as well as just plain crazy), but as far as I know, Johnny Depp does not listen to Mahler…

Perhaps because of the disproportionate focus on rich people just because they are rich, stereo stores appear to do very little to reach out to the people who have dedicated their lives to music—music teachers, church musicians, marching band directors, piano teachers, singing teachers, community chorus members, and the parents of serious young music students.

Why can’t a stereo store stay open on the night the TV series Glee is on and invite the regional high-school choral directors in for snacks and drinks and to listen to the TV show on a Home Theater system that was designed for music playback and not just for dinosaur footfalls? How about having an appreciation day for all the local piano teachers, with door prizes of great piano CDs?

Instead, most stereo-store events reach out to the same audiophiles who showed up last year. How about not letting audiophiles through the door unless they bring a non-audiophile, truly music-loving friend with them? Obviously, I am speaking only for myself here as a private individual and a music-loving record producer. I love audio and the audio industry, and I don’t want to see them drive the bus off a cliff.

We need to forget about rich people unless they are music lovers, and refocus on music lovers from all walks of life. To do that we have to be able to demonstrate an affordable system that clearly sounds better than what people already have in terms of their car stereo, computer audio, home theater, etc.

My first stereo system, adjusted for inflation, today would cost about $1,100. I think it would be great if a hi-fi show were to set up a special competition for systems costing no more than $1,100, and have a panel of impartial judges do the judging so there would be no problem with ballot-box stuffing.

I also think that the judging should be “binary.” “This system is excellent value for money: Yes or No.” No first, second or third prizes. Just a seal of approval: This system is excellent value for money. That allows for different tastes, and it makes the judging quick and easy.

If half of the systems get blue ribbons, great. If all of them get blue ribbons, that might be possible too. With a well-chosen receiver, plus some nice little two-way speakers, everything for $1,100 could be done. I think that it should be done.

I love expensive audio (as long as it sounds great). I know that it is a case of diminishing returns. I could not afford to buy the equipment I really love. But I also think that some external force has to impose a sanity check upon the industry and provide incentives to putting together and publicizing systems at the price points of $1,100, $2,500, and under $5,000.

As far as I know, the cost of the average “Stereophile” reader’s stereo system is about $17,000 (inflation-adjusted since that survey), but many of the new-product announcements I get seem to be for single pieces that cost more than that system total.

I think that dealers should give their stores a good hard look and see if they are doing all they could in the entry level and just as importantly, providing great choices in things to make up a $17,000 system, because that is where most of the market really seems to be.

How have multiple shows affected the audio world?

As I mentioned before, I think the reason that audio shows are now so important is that dealers are no longer as important, because there are so few of them compared to 20 years ago. That is in part because of changing consumer tastes, but also it is because compared to 20 years ago, the cost of running a first-class high-end store has to be so much higher.

I can remember when a $4000 DAC was shockingly expensive; now nobody blinks at a $4000 DAC. There are $40,000 “DAC Stacks” and supposedly $100,000 “DAC Stacks.” If a dealer is going to carry three major loudspeaker lines and three major electronics lines, and cables and headphones and turntables, what used to be a $100,000 inventory investment at dealer-demo prices now has to be more like $250,000.

And if you want to have the top of the lines on display, that investment goes up to $500,000. I speak in terms of a large store with up to five audio showrooms, and products such as Wilson Audio’s Alexandria XLF and the top items from Vacuum Tube Logic and dCS, and expensive cables, a nice turntable, etc.

That’s a lot of money to tie up in hopes that you will be the “last man standing.”

There is a lot more money to be made, more easily, in whole-home automation—lighting control and motorized window shades and the like. Furthermore, in that kind of business, nobody can waste your day listening to your gear and sucking up your knowledge base and then becoming an “educated shopper” trolling for used equipment on www.audiogon.com.

I think that a hi-fi show “exhaustion factor” may set in, and eventually manufacturers will have to look at the amount of money being spent on audio shows versus the incremental sales generated that would not come any other way. At some point, someone will say, “Nobody will think we are getting ready to go bankrupt just because we skip one audio show.”

It’s nice to say, “It should be all about the music.” However, a business needs to operate at a profit so that it can meet its obligations to its employees, its vendors, and its community. Most small businesses can’t operate profitably if they are spending $100,000 a year to ship gear and send out employees to shows all over the world, yet all that may be happening is that they are entertaining “tire kickers” who can’t or won’t buy the products. That’s throwing away $100,000 cash, which is sacrificing the profit on perhaps $500,000 of turnover.

I am NOT saying that hi-fi shows are a waste of money, any more than I would say that print-magazine advertising is a waste of money. But without question, all these hi-fi shows present a substantial financial burden, and at some point well-run companies have to justify such an expenditure.

A strictly audiophile question – is there a future for DSD files?

Well, what is a DSD file? And does it matter? All kinds of things can get turned into DSD. I am not going to turn my nose up at an SACD that started out as hi-res PCM such as DXD or 24/192. But I will object to an SACD that is only a format conversion of regular CD Red Book 16/44.1 data. Sony’s SACD of Glenn Gould’s 1982 Goldberg Variations was merely the CD data chopped up a different way. Then later they released a three-CD set that used the backup analog safety tapes. Why they did not use those analog tapes for the SACD—seeing as those tapes were edited on a Sonoma workstation for the CD re-release. Baffling.

When I see a hi-res PCM download or a DSD download offered for sale, I usually would like to see more information about the history of the project, the master tape, was there an analog backup, where did this data come from? I think there is not enough of that kind of information.

I think we are in a way going through the same “hi-fi demonstration record” phase as we did in early stereo, back then with freight trains and table-tennis games. People think they need a DSD DAC, and then they might play half a dozen “DSD” files, and then perhaps move on. On the best DACs available today, good Red Book CD sounds stunning.

|

The problem I have with hi-res music files of any kind for deep-catalog classical is that you end up having to print out the liner notes, and if needed, texts and translations. I think that SACDs are more practical, except that you can’t buy a transport that will output DSD via the DoP protocol—yet.

What is your current audio system?

Right now I am listening to Bricasti’s M1 DAC fed mostly from Parasound’s Halo CD 1 as a transport, Nordost digital cable, Cardas Clear analog cables, ATC’s P1 power amp, and ATC’s sealed-box SCM19 loudspeakers, which are a huge bargain at $3700 in the US. The ATC SCM19 is a great example of really delivering the goods for a very justifiable price. The whole system sounds fabulous.

What can web-based magazines learn from print magazines?

Perhaps, in some cases, a little more patience and perspective. The ecosystem of online publishing demands new content all the time. That can lead to what I call “The Tyranny of the New.” Other people used to call it “Flavor of the Month,” but now that has to be “week” or “day.” Writers should never forget the context of the things they have praised before. The newest can’t always be the best, can it?

There are things you learn about a piece of gear or a recording that come to the surface only after living with it a while. I find that my best judgments are retrospective, often times triggered by whether I miss a piece of gear after sending it back, or—am I glad it is gone, or at least, I don’t particularly miss it?

And what can print magazines learn from online magazines?

The magazines that have survived, I think have learned things from the web. I think that John Atkinson has struck a successful balance at Stereophile between new content going up on the website nearly every day, while the print magazine gives you the first look at in-depth reviews and measurements.

What is the most interesting technology you are aware of?

Two actually—the violin, and the concert grand piano. They fascinate me endlessly.

I mention those only because the human voice is a gift from God, and not a technology.

Is the “Loudness War” over yet?

Honestly, I hardly noticed it when it was going on. I don’t listen to much of the music that suffered most from the over-use of dynamic compression. I know that some reissues such as Born to Run came out with added dynamic compression, and that of course was regrettable. But a lot of the music I listen to, classical, jazz, and popular, was recorded in the 1950s. Some of those recordings will make you think that we actually have not advanced all that much.

What is the most natural recording technique for you?

That is a two-semester course. How much am I going to be paid to teach it?

The short answer is, that in order for something to sound “natural” in a totally different environment, we have to compensate in advance. That’s what makes recording an art based on science.

One fundamental problem is that in order to record so that there is a realistic stereo image, we often get an un-natural presentation because the microphones are much closer than your ears would be at a live performance. If you move the microphones back to get the tonal quality and the blended sound of a live performance as well as more hall sound, the stereo image becomes “wide mono.” This is why John Atkinson often records with three pairs of microphones in different arrays and at varying distances from the musicians, and time-aligns the three mic pairs in post-production.

Depending on what is being recorded, I love spaced omnis, Mid-Side, or ORTF. My default is ORTF. I try to be both a Neo-Platonist and an Aristotelean: If it sounds good, it is good.

A recording may be “impressive,” but if you don’t find yourself reaching for it to hear it again, there might be something artistically wrong, either in the performance or the engineering. Audio engineering is an art that you can’t reduce to a mathematical formula.

You usually end up giving up something once you decide that something else is more important. If you want all the bass and all the room sound you can get, you choose spaced omnis; but that choice is at the cost of not getting the in-focus, solid center image possible from coincident placement of directional microphones.

Could you list and describe 10 must-buy albums for the readers of “High Fidelity”?

Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, PORGY & BESS

Orchestra conducted by Russell Garcia

Produced by Norman Granz

Verve 827 475-2

Recorded Los Angeles, 1957

If there is one recording that best shows the complexity, the richness, and the depth of American musical life, this is it. No contest, as far as I am concerned. The story was written by a white Southerner and turned into an opera (with his help) by two Jewish brothers who were first-generation Americans. But the drama is universal.

At the emotional climax, the fallen woman Bess sings to the cripple Porgy that she is not worthy to stay with him because he is “too decent” to understand the hold that the drug pusher and pimp Crown has on her. There are many other things in opera and concert music that go as deeply into the mysteries of the human soul, and that similarly can be a sign of to us of the hope that love can offer. In my opinion, there is nothing that is clearly better; only different.

The men who sat around some rich guy’s table 500 years ago and invented opera, and Beethoven, and I think Mahler all would have been impressed, and emotionally moved. Of course, Fitzgerald and Armstrong almost can do no wrong, especially together.

Clifford Brown, CLIFFORD BROWN WITH STRINGS

Arranged by Neal Hefti

With Max Roach, Richie Powell, and George Morrow

Polygram 814 642-2

Recorded New York, 1955

Trumpeter Clifford Brown’s death at age 25 robbed the world of music of so many fair hopes. Some people feel a need to deprecate “with strings” projects. Well, Charlie Parker said that his favorite album was his ballad album with strings.

Clifford Brown’s songlike phrasing and tasteful ornamentation make this recording a high point in song-form jazz. Brown, of course, could blow Bop with the best of them, but here, it’s all about the melody, and phrasing, and tone. Technically, it is a shockingly good recording, given the date.

Frank Sinatra, Where Are You?

Arranged and conducted by Gordon Jenkins

MFSL CMFSA2109

Recorded Capitol Records Studio A, Hollywood, 1957

Sinatra was in some ways not a good person, and he ended up as a parody of himself. But while he was on his way back up, and had not yet started believing his own… nonsense, he made a few great albums. This I think is both the least-well-known, and the best of them. An amazing mono SACD transfer from MFSL; grab it while you can.

Sir Roland Hanna Tributaries, REFLECTIONS ON TOMMY FLANAGAN

IPO C1004

Recorded and mastered by Tim Martyn at S.U.N.Y., Purchase, NY, 2002

Roland Hanna’s tribute to his boyhood friend Tommy Flanagan turned out to be his last album. Excellent recorded sound, and pianism that reflects a lifetime’s accumulation of musical wisdom.

BASICALLY BULL

Alan Feinberg, pianist

Steinway & Sons 30019

Recorded at Sono Luminus, Boyce, Virginia, 2013

Playing early-keyboard music (circa 1611) written for the virginals or clavichord on a modern Steinway concert-grand piano sounds like a recipe for disaster. But, at least in this case, it was not. Alan Feinberg plays with delicacy and authority, and his selection of pieces holds your interest.

Cypress String Quartet, BEETHOVEN STRING QUARTET OP. 127 IN E-FLAT MAJOR

24/96-native recordings downloaded from www.cypressquartet.com

Recorded by Mark Willsher at Skywalker Sound, California, 2012

This young quartet from San Francisco has surprised me with a set of Late Quartets that has become my all-time favorite. The great recording job would be irrelevant if the playing were not so coherent and convincing. The web site has sound bites.

John Adams, THE DHARMA AT BIG SUR

Tracy Silverman, 6-string electric violin

BBC Symphony, John Adams

Nonesuch 79857-2

Recorded at Abbey Road Studios 2004/Skywalker Ranch 2006

Mastered by Bob Ludwig

The Dharma at Big Sur blends elements of Indian music, trance music, modal music, and electric-guitar-style virtuosity—in a two-movement work for six-string electric violin and orchestra. However, I think that when you carefully scrape away the overpainting, what is underneath is a traditional 19th-century virtuoso violin concerto. In other words, music that Paganini or Wieniawski could relate to—and so can you.

Elvis Costello & The Attractions, ALL THIS USELESS BEAUTY

Warner Bros. 46198

Produced by Geoff Emerick and Elvis Costello

Recorded at Windmill Lane, Dublin and Westside Studios, London 1995-1996

Mastered by Bob Ludwig

The fuss made over Justin Bieber would seem to indicate that the music-business conventional wisdom I heard a long time ago is most likely still true. That is, the largest single demographic segment of buyers of recorded music is girls 16 years and younger. Not yet having driver’s licenses or jobs, they tend to stay home or socialize with other girls; listening to music is often a shared activity. Unsurprisingly, that audience does not demand complexity or ambiguity in the music they enjoy.

Complexity, ambiguity, and perhaps even a reappraisal of the place of rock music in the cosmos is what you get with Elvis Costello’s All This Useless Beauty, his seventeenth studio album (1996). It’s a shame that the liner notes’ presentation of the songs’ lyrics is nearly indecipherable. There are some deep and somewhat scary things going on in these songs. Along with, it seems, quite a load of barely-repressed anger.

What makes this recording a sure recommendation to audiophiles, however, is the sheer impact of the recorded sound, coupled with so much fine detail. Each track creates its own sound-world.

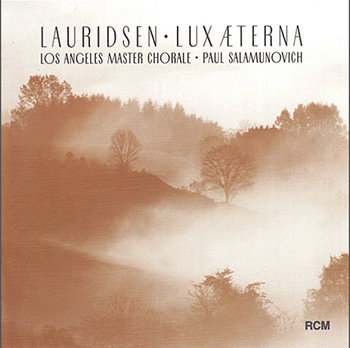

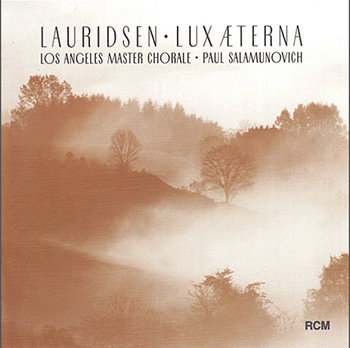

Morten Lauridsen, LUX ÆTERNA, OTHER WORKS

Los Angeles Master Chorale, Los Angeles Master Chorale Sinfonia Orchestra, Paul Salamunovich

RCM 19705

Peter Rutenberg, producer; Fred Vogel, engineer

Recorded in Sacred Heart Chapel, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles 1997 & 1998

How’s this for unlikely? An American composer (and former jazz-flugelhorn player) writes a five-movement Latin-language (but non-liturgical) Requiem for chorus (with orchestra in the four outer movements). To a degree, Lauridsen emulates the architecture of Brahms’ Ein deuteches Requiem. His Requiem’s surprising underground/grassroots success has made it one of the most-performed works for chorus and orchestra written in the 20th century, eclipsing works by Elgar, Stravinsky, and Leonard Bernstein. The vocal score has sold more than 300,000 copies.

Lux Æterna shows a subtle mastery of formal structure as well as complete familiarity with the history of choral music. It reveals a wealth of inspired ideas, one of the most pivotal being the decision to do without vocal soloists. I think that the work is concise enough and holds one’s interest well enough not to need the addition of vocal soloists, given the risk that they would become quasi-operatic distractions.

For all its thousands of live performances, Lux Æterna has only been recorded for commercial release four times; to my knowledge, no “name” orchestra has ever presented it.

Holst, THE PLANETS

Boston Symphony Orchestra, William Steinberg

Deutsche Grammophon 419 475-2; other couplings available; 24/96 downloads available from HDTracks.com

Karl Faust, Tom Mowrey, producers; Günter Hermanns, engineer

Recorded in Symphony Hall, Boston, Massachusetts, 1971

The Planets is pretty much the definitional “crowd-pleasing orchestral warhorse.” However, there are legitimate reasons for its widespread popularity, including the inspired orchestrations, the brevity of the movements (which alternate between drama and repose), and some memorably rollicking “big tunes.”

There are at least 40 available recordings of The Planets. A very small handful accounts for the versions most frequently recommended (Boult, Mehta, and Previn, it seems to me). For whatever reason (or no reason) the Steinberg/Boston Symphony recording seldom gets the praise it deserves. The Boston Symphony was still basking in the glow of its golden era. The tempi are brisk, the ensemble tight, and the recorded sound among the best ever recorded in Symphony Hall.

Single tracks not available individually, but the 24/96 full-album download is reasonably priced. Used LPs and CDs widely available, and perhaps your local library has a copy.

In “THE EDITORS” series we have interviewed so far

ART DUDLEY, “Stereophile”, USA, editor-at-large, interviewed HERE

Helmut Hack, “Image Hi-Fi”, Germany, managing editor, interviewed HERE

Dirk Sommer, „HiFiStatement.net”, Germany, chief editor, interviewed HERE

Marja & Henk, „6moons.com”, Switzerland, journalists, interviewed HERE

Matej Isak, "Mono & Stereo”, chief editor/owner, Slovenia/Austria; interviewed HERE

Dr. David W. Robinson, "Positive Feedback Online", USA, chief editor/co-owner; interviewed HERE

Jeff Dorgay, “TONEAudio”, USA, publisher; interviewed HERE

Cai Brockmann, “FIDELITY”, Germany, chief editor; interviewed HERE

Steven R. Rochlin, “Enjoy the Music.com”, USA, chief editor; interviewed HERE

Stephen Mejias, “Stereophile”, USA, assistant editor; interviewed HERE

Martin Colloms, “HIFICRITIC”, Great Britain, publisher and editor; interviewed HERE

Ken Kessler, “Hi-Fi News & Record Review”, Great Britain, senior contributing editor; interviewed HERE

Michael Fremer, “Stereophile”, USA, senior contributing editor; interview HERE

Srajan Ebaen, “6moons.com”, Switzerland, chief editor; interviewed HERE

|

ave a look at the pictures in John Marx’s listening room. What do you see? What caught your attention? I was struck by the ubiquity of records and the ATC standmount speakers placed upside down. They point to John’s "out-of-the-box" thinking on the one hand and to his love for music. This is not just another audiophile with three CDs (samplers) to review audio components or someone who shudders at every single “non-kosher” detail.

John is, among other things, an audio journalist who has been running Stereophile’s Fifth Element column for years. His essays, articles, and reviews are different than what is usually found in audio magazines. They focus on the music and the man, treating the audio system as a necessary, viable and valuable tool, but a tool nonetheless which can be used well or poorly. The last thing you could say about him is that he "fetishes" hi-fi audio. His passion for audio gear is evident, otherwise he would not have spent time on it. But when he starts talking about the music everything else pales in comparison.

ave a look at the pictures in John Marx’s listening room. What do you see? What caught your attention? I was struck by the ubiquity of records and the ATC standmount speakers placed upside down. They point to John’s "out-of-the-box" thinking on the one hand and to his love for music. This is not just another audiophile with three CDs (samplers) to review audio components or someone who shudders at every single “non-kosher” detail.

John is, among other things, an audio journalist who has been running Stereophile’s Fifth Element column for years. His essays, articles, and reviews are different than what is usually found in audio magazines. They focus on the music and the man, treating the audio system as a necessary, viable and valuable tool, but a tool nonetheless which can be used well or poorly. The last thing you could say about him is that he "fetishes" hi-fi audio. His passion for audio gear is evident, otherwise he would not have spent time on it. But when he starts talking about the music everything else pales in comparison.